|

| Samuel Gorton (artist unknown) |

In Colonial America, clashing loyalties and disparate religious beliefs often resulted in breakaway groups of colonists departing to form new settlements.

The earliest English immigrants to the British colonies were typically separatists; Puritans so extreme that they had to cross an ocean and start a new civilization in order to adequately distance themselves from an English church they viewed as ungodly and corrupt. In history class, we learn that the Puritans came to America seeking religious freedom, and this is partially correct, but that freedom only extended to those who worshipped like they did. They were incredibly intolerant of those who practiced other forms of Christianity. Anglicans, Quakers, and Antinomians were not welcome in Puritan societies. Any behavior that deviated from the strict, scripture-based laws of these new colonies was punished harshly and publicly. As the 1600s progressed, and more people started arriving from England, inevitably not all of them fit into the world the separatists had created, leading to increased conflict.

Another issue that festered in the background during these first decades in America was the issue of ultimate authority. Early voyages to America had been organized by religious groups or leaders, with the support of a benefactor, but these organizations did not necessarily communicate with each other or have the foresight to work together. Colonists sometimes arrived to create a community in a particular location, only to find it already taken. There were competing interests, both in England and the colonies, and companies sponsoring immigrants morphed, dissolved, or merged in ways that made governance challenging for those living in disputed areas. The colonies were not one big country with different cities and states, as New England is now. It was essentially a patchwork of small countries, governed by different parties in England, with rules enforced by local leaders, and not necessarily welcoming to new settlers. In short, everyone could not just get along. It was complicated.

|

| Map of New England printed by John Seller John in 1675 CE, based on William Reed's original survey of 1665 CE. |

When my 9th great-grandfather, Samuel Gorton, arrived in Massachusetts in 1637, the settlements there were reeling from the Antinomian Controversy. This controversy set the followers of radical minister John Cotton, namely the strident Anne Hutchinson and her brother-in-law John Wheelwright, against traditional Puritans, like Massachusetts Bay Company Governor John Winthrop. I discussed this moment in history in my post about my 11th great-grandfather Robert Moulton, who was disarmed in Salem for supporting Anne Hutchinson's right to worship as she desired. Cotton, Wheelwright, and Hutchinson were gathering followers as they evangelized, teaching that strict obedience was unnecessary for salvation, and that faith alone was the answer. The Puritans thought they were heretics and chased them out of Massachusetts. The animosity their proselytizing created was a true crisis for this young colony.

To further set the stage, in the 1630s, Rhode Island did not yet exist. Scattered communities had been established, largely as outposts for those not welcome in Massachusetts, but there was not yet connective thread between them.

Although the Puritan British theologian Roger Williams is often given the sole role of founder of Rhode Island, the colony was in fact settled by five independent and combative sets of people between 1636 and 1642. They were all English, and most of them began their colonial experiences in Massachusetts Bay colony but were banished for various reasons. Roger Williams' group was the earliest: In 1636, he settled in what would become Providence on the north end of Narragansett Bay, after he was kicked out of the Massachusetts Bay colony. [source: ThoughtCo]

The early Rhode Island settlements included Providence, Portsmouth, Newport, and Warwick.

The settlement at Providence along the Narragansett Bay, established by Williams and his followers in 1636, soon became a haven for religious dissidents. In 1644 Williams obtained a patent for the colony of Providence Plantations, later Rhode Island. [source: Library of Congress]

Meanwhile, another community was taking shape on an island off the coast, founded by William Coddington.

In 1637 he [Coddington] supported the controversial antinomian religious tenets of Anne Hutchinson, and as a result he and his followers were obliged to leave Massachusetts for the island of Aquidneck (Rhode Island) in Narragansett Bay. Coddington established a government based on Old Testament precepts in a settlement that he led at Pocasset (Portsmouth) on the northern part of Aquidneck. Anne Hutchinson had also settled in Portsmouth after she was banished from Massachusetts, but Coddington became embroiled in a dispute with her and moved his settlement to Newport in 1639. Although Portsmouth and Newport were united the next year, with Coddington elected governor, his hopes to maintain the island of Aquidneck as a separate colony were thwarted in 1644, when the English colonist Roger Williams obtained a patent uniting his Providence plantations with Aquidneck. [source: Brittanica]For more information on this fascinating period in early America, I recommend listening to The Other States of America History Podcast's episode Rhode Island Versus Providence Plantations: Shawomet, Portsmouth, Newport and Providence (1643-1663).

|

| A painting by artist Jean Blackburn depicting the town of Providence about 1650. |

Samuel Gorton was married before January 11, 1629/30 to Mary Mayplet, the daughter of haberdasher John Mayplet. Mary was the granddaughter of the Reverend John Mayplet, Rector of Great Leighs Parish in Essex, Vicar of Northolt in Middlesex, and a writer on the topics of natural history and astrology. Her brother was Dr. John Mayplet, physician to King Charles II. [source: Wikipedia]

Mary was also educated and could both read and write, skills that were not typically prioritized for women during that time. Samuel and Mary had nine children together, the eldest two born in England.

- Samuel Gorton (b. 1630; d. 1723; m. Susanna Burton)

- Mary Gorton (b. 1631; d. 1688; m. (1) Peter Greene (2) John Sanford)

- Sarah Gorton (b. 1638; m. William Mace (or Mayes))

- John Gorton (b. 1640; d. 1714; m. Margaret Wheaton)

- Elizabeth Gorton (b. 1641; d. 1704; m. John Crandall)

- Mahashalalhasbaz* Gorton (b. 1642; d. 1692; m. Daniel Coles)

- Anna Gorton (b. 1644; d. 1734; m. Daniel Warner)

- Susanna Gorton (b. 1649; d. 1734; m. Benjamin Barton)

- Benjamin Gorton (b. 1650; d. 1699; m. Sarah Carder)

Samuel's life would come to be defined by his particular religious beliefs, which did not align with any of the prevailing forms of Christianity at the time. In comparing his orthodoxy to other religions, it was perhaps most similar to Quakerism, but definitely unique to Gorton.

[Gorton] rejected any partnership between religion and the civil authorities and any outward trappings of worship, denied the Trinity, accepted the divinity of Christ, rejected a “hireling ministry” (i.e., a paid clergy), and asserted that he was the mere instrument by which the Holy Spirit spoke to his followers. [source: RIHeritageHallofFame]

Gorton also sponsored one of the first laws for the emancipation of slaves. He believed in freedom of worship and even was willing to grant that right to Quakers. He felt that immortality depended on the total character. He opposed rituals and denied the doctrine of the Trinity. Gorton was a compelling lay preacher and a brilliant scholar and dubbed himself ‘professor of the mysteries of Christ.' [source: Robert F. Huber, “Gorton Gets the Boot,” The Howland Quarterly, Vol. 65, No. 4, (December, 2000).]

Samuel had strong religious beliefs but sometimes little patience for his neighbors. Perhaps due to his high level of education and success in business, and likely owing to his absolute certainty about the divine, he repeatedly engaged in conflicts with those he found ignorant, unlawful, or disrespectful. While these sorts of incidents were not documented until he arrived in Massachusetts, it's fairly certain they occurred before he departed for the colonies, as well. The English did not appreciate the fervor of the Puritans, and they likely felt the same about Samuel Gorton and his proselytizing. Given Samuel's financial security in London, his departure for the colonies seems to have based in a quest for religious freedom, and the opportunity to gather like-minded supporters.

|

| A depiction of the type of ship that would have brought the Gortons to the colonies |

In late 1636 or early 1637, Samuel, Mary, and their two children sailed from London to Boston. Samuel arrived in Massachusetts with out-of-the-box religious persuasions and a personality that was an acquired taste. Neither went down well with the Bostonians.

Perhaps my favorite publication about Samuel Gorton is the New England Historical Society's article, Samuel Gorton Insults the Puritans, Goes to Jail, Founds Warwick, R.I., with the tagline, "He believed in equality for all, but he was obnoxious about it." The URL for this article includes, "Samuel Gorton and His Gortonites Create a Church Amongst the Jack an Apes." It is hilarious, and makes light of the many years in which Samuel engaged in rather outrageous conflicts with neighbors, the Massachusetts Bay Company, Roger Williams, and anyone who got in his way. However, recent history has reconsidered the longstanding view of Gorton as the ultimate antagonist in early New England.

The "cantankerous", "contumacious" and "obnoxious" Samuel Gorton has been subject to misrepresentation by the historians of four centuries. He is most commonly described as "bewitching and bemadding" not only Providence but the whole of southern New England. Edward Winslow's contemporaneous Hypocrisie Unmasked is the usual starting point for those seeking an introduction to Samuel Gorton, appearing as it does to consist of testimony from several sources, including John Winthrop, of Gorton's "mutinous ...seditious ...uncivil ....riotous" and "licentious" behaviour. But Hypocrisie Unmasked was composed at the specific request of the government of Massachusetts with the expressed purpose of discrediting Gorton before the English government. Gorton's own testimony in Simplicities Defence and elsewhere tells a different story, which whilst not contradicted in his lifetime, or since, has not been thoroughly researched in its own right. Far from being the "dangerous" and "crazed thinker" of tradition Samuel Gorton was in fact a "strenuous beneficent force", whose importance to the independence of the colony of Rhode Island, and his courage in securing it, was matched only by Roger Williams. [source: G. J. Gadman, "A strenuous beneficent force": The Case for Revision of the Career of Samuel Gorton, Rhode Island Radical']

Samuel and his family landed in Boston and soon moved to Plymouth Colony. There, in addition to attending the local church, Samuel began to gather with others in his home to share his own personal theology. These meetings were open to those frequently marginalized in Puritan churches, including women. Having just expelled Anne Hutchinson, Massachusetts religious and civil authorities were wary of another charismatic leader preaching a belief system that differed from theirs. They asked Samuel's landlord to evict him. At the same time, Samuel was testifying in court in defense of his household's maid, who was being threatened with banishment for smiling in church. Since he was there, local officials took the opportunity to enforce his eviction. Samuel "challenged the court for abusing procedure and appealed to the people to 'stand for your liberty'. For this he was accused of "sedition" and "mutiny", fined £20 and banished." [Source: FamousAmericans] Samuel and two of his supporters, John Wickes and Thomas Wickes, were given 14 days to leave Massachusetts entirely. Unfortunately, this eviction occurred during a terrible winter blizzard, and while the men were able to entice neighbors to take in their wives and children, Samuel, John, and Thomas were forced out into extreme weather to find shelter in unsettled wilderness.

Samuel headed to the colony at Portsmouth that had been founded in 1638 by religious dissenters from Massachusetts Bay Colony, including John Clarke, William Coddington, and the infamous Anne Hutchinson. Samuel and his family settled on some land there, but soon ran into trouble again. Samuel immediately got involved in a simmering feud regarding the separation of Portsmouth and Newport, making no friends in the process. Also, there was apparently a bit of a racket going in Portsmouth, where farmers would cut the fences of other farmers, allowing their neighbors' cattle to roam freely. Then, they would complain that the cows had damaged their property and demand compensation. When this happened to Samuel, did he pay the fine and move on? Of course not. This was exactly the kind of dishonest and unlawful behavior that Samuel hated with a passion (and frankly, this sentiment still runs in the family). He went to court over the matter, made indignant and passionate speeches in his defense, refused to back down, and when the court fined him, Samuel called them "asses." He called his neighbors "jack-an-apes" and "saucy boys." He was not having any of it. For his trouble, he was whipped and banished.

|

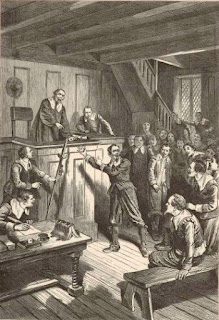

| William Coddington sits as judge in the trial of Samuel Gorton in colonial Rhode Island (artwork created in 1876) |

Samuel moved on to Providence, founded by Roger Williams, but once there, he refused to accept the authority of the colonial government, as he believed that only England and the King had jurisdiction. Roger Williams refused to grant him freeman status because he would not submit to colonial authority or denounce his behavior in Portsmouth. Tensions grew between Gorton's supporters, who numbered quite a large group at this point, and Providence authorities. It erupted into a street riot in November 1641, at which point Gorton fled south for Pawtuxet, rightly fearing retribution.

|

| Another rendering of Gorton in court, by Granger |

Pawtuxet wanted nothing to do with Samuel, whose reputation preceded him. Despite being well outside the boundaries of Massachusetts, Pawtuxet officials appealed to the Massachusetts Bay Company to come and get Samuel, offering to allow them jurisdiction in Pawtuxet. Samuel got the message and split, but where was a radical religious leader and his band of followers to go, having been exiled from the entirety of Massachusetts and three separate communities in the future Rhode Island?

Samuel found a refuge at Shawomet (later Warwick), which was five miles south of Pawtuxet and thirty miles beyond the Massachusetts border, thus theoretically safe from threats. He and his supporters purchased land from the native Narragansett people living nearby, and hoped to set up a permanent refuge, living in harmony with their Narragansett neighbors. However, the officials in Pawtuxet felt Samuel was still too close for comfort. They enticed two Narragansett sachems to complain to the Massachusetts Bay Company that their lands had been stolen, not purchased. Gorton was summoned to Boston to respond to the accusation, but because Samuel did not recognize colonial governments, he refused to go. In September 1643, Massachusetts sent forty soldiers to Shawomet, where they attacked the village, causing panic and the deaths of two women. After a standoff, Samuel and several supporters were arrested and marched back to Boston. "The attack by Massachusetts soldiers on the Gortonists in Shawomet in 1643 has been called one of the greatest crimes of the colonial period." [source: Warwick Beacon]

|

| Attack on Shawomet by soldiers from Massachusetts in 1643 (Scribner's Popular History of the United States, 1898, by William Cullen Bryant, Sydney Howard Gay, Noah Brooks) |

In Boston, Samuel was tried and quickly convicted. The magistrates were divided on whether he should get a death sentence, so instead he was shipped to Charlestown, put in irons, and sentenced to work. However, Gorton could not keep quiet. Even as a prisoner, he was still allowed to go to church, and he regaled everyone he encountered there with tales of his mistreatment and the corrupt Massachusetts court. The magistrates were not about to let this spiral into an uprising, so they released Gorton and again gave him 14 days to get out of Massachusetts, but declared he could not return to Providence or Shawomet. And then they changed the amount of time he had to vacate the colony to two hours.

The colonial leaders in Boston also took this moment to shore up their power in Rhode Island by turning Native American groups against each other in order to weaken their influence.

The Boston authorities, seeking to make their claim even more secure by dividing the Indians, decided to eliminate Miantonomi [leader of the Narragansett people] as well. They prevailed upon Uncas, chief sachem of the Mohegans, to make war on the Narragansetts, and promised him help and money. Miantonomi and his warriors were led into a trap and Miantonomi was captured. The Mohegan sachem Uncas, seeking to curry even more favor with the English, beheaded Miantonomi, and sent the grisly trophy to Boston. This proved to be Boston’s undoing in Shawomet, for when Samuel Gorton returned to get his belongings, he was greeted by sadder but wiser groups. Indians, angered at the Massachusetts authorities for the part they played in the disgraceful treatment of Miantonomi, felt that any treaties with the Massachusetts authorities were no longer binding on them. Because Gorton was freed, they believed he had more power than the Massachusetts authorities. Gorton easily persuaded the Narragansetts to sign a treaty placing themselves under the protection of the King of England, and to confirm his claims to Shawomet. [source: Warwick Beacon]

Samuel temporarily returned to Portsmouth, where William Coddington gave him refuge, despite their past conflicts. However, it became clear that Coddington could not truly protect Samuel from his many enemies, and Portsmouth would be no safe haven. Samuel decided his only option was to sail to England, along with several of his followers, and attempt to garner support from someone of importance there.

In the four years he spent in England, away from his family and followers, who remained at Shawomet, Gorton was productive. He wrote extensively about his faith and his experiences in the colonies, including, in 1646, a tract titled Simplicity's Defence Against Seven Headed Policy, which dealt specifically with the injustices inflicted upon the settlers at Shawomet. Working his connections, Samuel was able to garner support for Shawomet from Robert Rich, the second Earl of Warwick, who wrote him a letter authorizing safe passage back to Shawomet, and endorsed his quest to receive a royal charter for the settlement. In 1648, bearing this letter, Samuel sailed boldly into Boston Harbor. He was immediately arrested.

|

| Artwork depicting the moment Gorton gave Warwick's letter to Massachusetts authorities |

Once the Massachusetts Bay Colony authorities saw Gorton's official order of protection for Shawomet, signed by the Earl of Warwick, they had no choice but to release him and allow him to continue to Shawomet. Samuel returned to Shawomet victorious. He was greeted as a hero by his supporters, and they promptly renamed Shawomet in honor of the Earl who gave them legitimacy and protection, Warwick.

Gorton's views on the role of government had transformed markedly during his time in England. He became actively involved in roles that he had previously criticized, now that his settlement of Warwick was secured by royal decree. The separate settlements of Providence Plantations, Portsmouth, Newport, and now Warwick all came together under a fragile government, choosing John Coggeshall as its first President in 1647 and calling itself the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. With his success in England, Gorton was seen as a leader in the colony and he was chosen as the Warwick assistant (magistrate) in 1649 under colonial President John Smith, also from Warwick. Both Gorton and Smith declined their positions but were fined for doing so; they both ultimately served and their fines were remitted. [Source: Wikipedia]

Samuel Gorton spent the rest of his life in Warwick, engaging in a number of leadership and regional government roles. In 1651, he was chosen as President of the Rhode Island colony. During this time, he wrote a bold statute that was ahead of its time, an act calling for the emancipation of slaves.

As early as 1652, Warwick’s founder, Samuel Gorton, then president of the colony, called for a general assembly that ordered that “no slave, black or white, could be held in servitude for more than ten years.” This was one of the first laws in English colonies to provide for emancipation. After a great deal of deliberation and discussion in the press, Rhode Island called for freedom for “all children born of slave mothers” after the first of March 1784. [Source: Cranston Herald]

In the spring of 1677, Warwick was destroyed during King Philip's War. The townspeople, who fled ahead of the violence, returned to a community that had been burned to the ground and had to be completely rebuilt.

|

| The grave of Samuel Gorton |

Samuel Gorton died in late 1677, after having returned to Warwick and supported rebuilding efforts. He was about 84 years old. It is not known precisely when his wife Mary died, but she was still alive in April 1670, when her brother John mentioned her in his will. They left nine children, including my 9th great-grandmother, Mahashalalhasbaz Gorton Coles, and numerous grandchildren, including my 8th great-grandfather, Samuel Coles.

Early Rhode Island historian Samuel G. Arnold would write of Samuel Gorton, “He was one of the most remarkable men that ever lived. His career furnishes an apt illustration of radicalism in action, which may spring from ultra-conservatism in theory. The turbulence of his earlier history was the result of a disregard for existing law, because it was not based upon what he held to be the only legitimate source of power—the assent of the supreme authority in England. He denied the right of a people to self-government, and contended for his views with the vigor of an unrivalled intellect and the strength of an ungoverned passion. But when this point was conceded, by the securing of a Patent, no man was more submissive to delegated law. His astuteness of mind and his Biblical learning made him a formidable opponent of the Puritan hierarchy, while his ardent love of liberty, when it was once guaranteed, caused him to embrace with fervor the principles that gave origin to Rhode Island.” [source: Small State Big History]

I'm also related to another notable figure in the history of Rhode Island, Robert Coles. My 9th great grandfather will be the subject of my next post. In addition to his role in the founding of Rhode Island, Robert was the inspiration for a work of classic American literature.

No comments:

Post a Comment