I had never seen anything like this and had never heard of trench art. What was this, exactly? I consulted Google. On the website trenchart.org (which quotes heavily from Jane Kimball's book, Trench Art: An Illustrated History), I found the following description:

Pieces described as trench art have the following distinctly different origins:

- War souvenirs collected by soldiers or non-combatants during the war and during the demobilization period and modified in some way to serve as a remembrance of the war.

- Souvenirs crafted by soldiers during the war.

- Souvenirs made for sale to soldiers by other soldiers or civilians during the war.

- Souvenirs made by prisoners of war in exchange for food, cigarettes or money.

- Mementoes of the war made by convalescent soldiers.

- Post-war souvenirs made for tourists visiting the battlefields.

- Post-war souvenirs made by commercial firms in trench-art style.

My brother was able to tell me a little more about George's unique piece of trench art and the engravings on the shell itself give hints as to its place and year of origin.

|

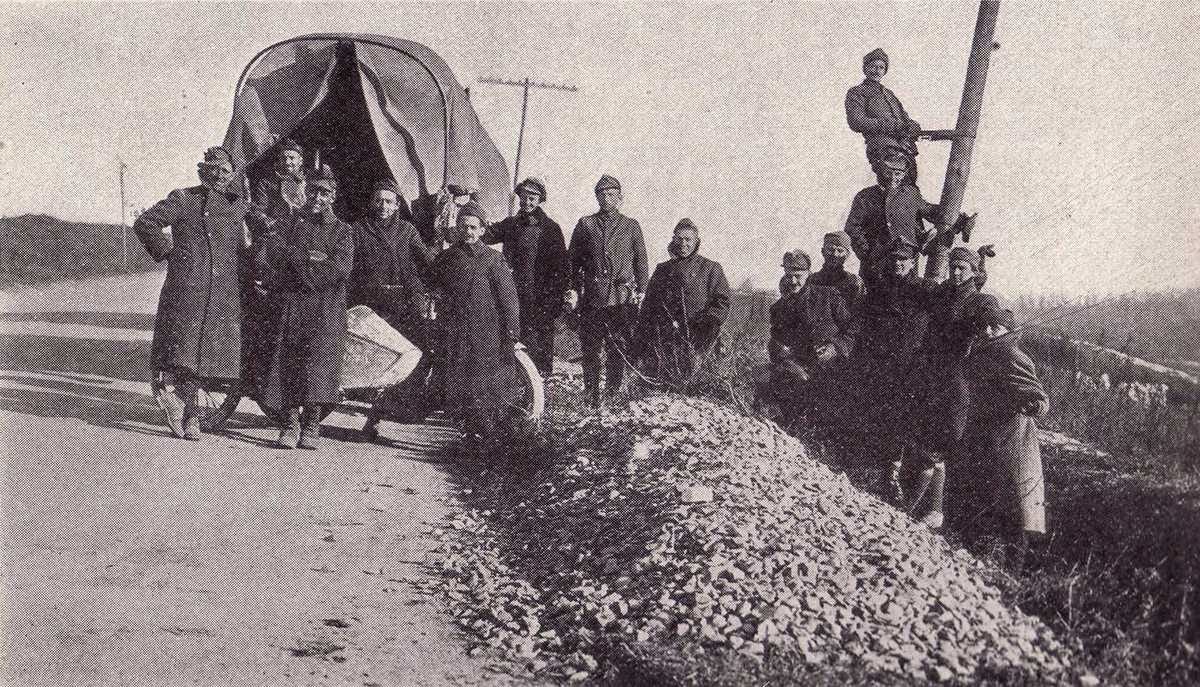

| A Canon de 75 Modele 1897 in use in World War I. [source] |

The shell has been hammered into a vase or tall drinking cup. It reads, "1918 St. Mihiel." As readers of this blog know, George Rutherfurd was one of the first Americans to enter the French town of St. Mihiel after it was bombarded by German forces in September 1918. During his time there, he either bought or was given this piece of trench art. My brother says he was told that the St. Mihiel villagers made this and other items of trench art with the shell casings that littered their town after the battle.

The bottom of George's piece of trench art is marked with the following information: 75 DE C MGM 449L 1/ USA. I've been doing a lot of reading about the markings on shell casings to see what this might mean. The best that I can tell, this is a 75mm De Campagne (or "field gun") shell. It was almost certainly shot by a Canon de 75 Model 1897, a fast-acting piece of artillery commonly in use by the French Army and American Expeditionary Forces in World War I. The letters MGM should refer to the maker of the shell. I think this might mean it was made by Metropolitan Gas Meter Co., which was an English company. However, it clearly says USA, so perhaps not. If an expert on trench art happens upon this post, I'd love more information.

|

| This image from WWI shows a mounted Canon de 75 Modele 1897 field gun in action. [source] |

The people of St. Mihiel had experienced the full force of war and their town was heavily damaged. Yet, whether out of the simple need to make money or the desire to transform something ugly into something beautiful, someone in St. Mihiel created this unique item. It then traveled from France to New Jersey, through the Panama Canal, to San Francisco, to Los Angeles, and finally to George Rutherfurd's last home in San Diego County. My brother now owns a World War I shell casing, nearly a century after it fell on St. Mihiel.