Today, it has been 77 years since my grandmother's cousin, Gil Cook, died over Burma. I have written about Gil and this family tragedy many times, but in honor of this sad anniversary, am sharing a summary of Gil's life and service. Lawrence Gilbert Cook, known as “Gil,” was born in Los Angeles on July 24, 1918. He was the son of Magdalene Barrett and Lawrence Cook, who divorced when Gil was a small child. Gil was just a few weeks older than my grandmother, LaVerne Rutherfurd, who was born in Los Angeles on August 10, 1918, and he was the closest thing to a sibling that she had. In their early years, they lived down the street from each other and spent a lot of time together.

|

| (L-R): LaVerne Rutherfurd, Gil Cook, and Gil's mother, Magdalene Barrett |

|

| (L) LaVerne Rutherfurd and (R) Gil Cook |

Magdalene Barrett remarried Bob Rutherfurd and in 1928, Gil’s sister Patricia Mary “Patty” Rutherfurd was born. The family lived together in Los Angeles, then moved south to San Pedro, Wilmington and Long Beach.

On February 27, 1941, at the age of 22, Gil enlisted in the United States Army. While America had not yet entered World War II, war was certainly on the horizon. On his enlistment paperwork, Gil, a high school graduate, listed his occupation as “Frameman, Telephone and Telegraph.” Much of the family worked in the telephone business. His mother had been a telephone operator, as had his aunt Julia Barrett Rutherfurd. Julia and her husband George Rutherfurd (half brother of Gil’s stepfather Bob) had met while working at Pacific Telephone and Telegraph in Los Angeles.

Gil enlisted as a private and later became a second lieutenant. He was assigned to the Army Air Corps, serving in the 436th Bombardment Squadron. Between 1941 and 1943, Gil underwent training at several different locations, including Vancouver, Washington, Douglas, Arizona, and finally Topeka, Kansas. Throughout his training, Gil wrote letters home to his mother, sharing stories about his experiences and asking after family members and friends.

Gil was also writing to his girlfriend, Ethel Hamel, the young woman he'd been dating before leaving for service. Ethel Hamel was the youngest daughter of Eugene Hamel and Rose Huot of Alberta, Canada. The Hamel family had a second home in Long Beach, where Gil Cook lived, and eventually moved there full time after the death of Ethel's father. The story of how Gil and Ethel met has not survived the years, but they quickly grew close and the relationship became serious.

In letters sent to his mother, Gil mentioned that he had been saving money for a ring. Gil and Ethel became engaged in 1943. He may have been headed for war, but Gil was planning for a life with the woman he loved.

|

| Gil Cook and Ethel Hamel |

|

| Gil Cook and Ethel Hamel |

In Topeka, Gil was assigned to a plane and a crew. There were nine young men, including Gil, who made up this B-24 Liberator crew. In training, they grew close. Gil became especially good friends with Joe Zofco, who was the son of Czech immigrants from Ohio.

|

| Gil Cook and Joe Zofco |

|

| The four photos above were taken of Gil Cook during training |

April 25, 1943: Florida to Trinidad

April 28, 1943: Trinidad to Belem, Brazil

May 5, 1943: Belem to Ascension Island, in the Atlantic Ocean

May 9, 1943: Ascension Island to Accra, Ghana

May 10, 1943: Accra to Kano, Nigeria

Gil Cook and Joe Zofco in Africa

Donald Morris, James Reese, Edward Perrin In Africa

Charles Davis, Donald Morris, John Wood

Gil's journal ends in Nigeria, but not long after this, he and his crew arrived in India and joined the 436th Bombardment Squadron assembled there.

On October 28, 1943, 25-year old Gil Cook's plane went down over Burma in a friendly fire incident. There were nine crew members on board. There were no survivors.

On November 7, 1943, witnesses to the plane's accident were deposed by the Army. Their statements are the clearest indication we have of exactly what happened to Gil and his crew. Unfortunately, it would take months for these details to be revealed to the airmen's families, during which time they hoped desperately that the "missing in action" designation meant their loved ones would eventually be found alive. It was not to be.

From the statement given by Warren J. Chadwick, S/Sgt, Air Corps, 436th Bombardment Sq. (H):

From the statement given by Arthur J. Darling, T/Sgt, Air Corps, 436th Bombardment Sq. (H):

This letter did not clarify that Gil's plane had been struck by a bomb dropped by an American plane. It also did not give Magdalene the news that her son was surely dead.

In Kansas City, Jane Luce, fiancee of the plane's pilot, Jim Reese, had also learned that Reese's plane was missing. She sprung into action, finding an address for Magdalene Barrett Rutherfurd via the Red Cross and writing to her to share information.

For the balance of the war, [the 436th Bombardment Squadron] carried out long distance heavy bomb raids over Japanese targets primarily in Burma, Thailand and Indochina; a theater with little news coverage, see China Burma India Theater; although also attacked Japanese targets in Southeastern China attacking airfields, fuel and supply dumps, locomotive works, railways, bridges, docks, warehouses, shipping, and troop concentrations in Burma and struck oil refineries in Thailand, power plants in China and enemy shipping in the Andaman Sea.1

(L-R:) James M. Reese, William Jerabek, Edward M. Pyle,

Joseph A. Zofco (in front), Donald P. Morris, John P. Wood, Gil Cook

On September 18, 1943, Gil wrote a letter to his uncle saying that there hadn't been much flying time due to monsoon season, but that the weather was improving and he'd been on five missions in seven days, completing eleven runs total since his arrival.

|

| This was included in a stack of paperwork related to Gil Cook sent to me by the National Archives |

On October 25, 1943, Gil wrote his last letters home. In a letter to his mother, he said that he was looking forward to an expected trip home in 1944 and asked her to send some gramophone needles so he could listen to music. In a letter to his fiancee, Ethel, he said how much he missed her and talked about their future children.

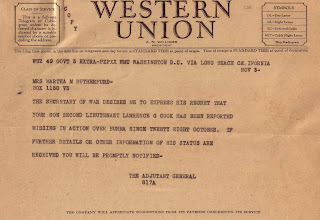

On November 3, 1943, Gil's mother, Magdalene Barrett Rutherfurd, received a telegram reporting him missing in action.

On November 7, 1943, witnesses to the plane's accident were deposed by the Army. Their statements are the clearest indication we have of exactly what happened to Gil and his crew. Unfortunately, it would take months for these details to be revealed to the airmen's families, during which time they hoped desperately that the "missing in action" designation meant their loved ones would eventually be found alive. It was not to be.

From the statement given by Warren J. Chadwick, S/Sgt, Air Corps, 436th Bombardment Sq. (H):

On or about October 28, 1943 at approximately 1217 hours, I, S/Sgt Warren J. Chadwick, 19020370, while flying as right waist gunner in #2 position of the first element, observed the following: We were on our 2nd run when a three ship formation echeloned over our 2nd element. I saw two bombs drop from the ships above, one dropping between #2 engine and the fuselage of the ship hit. The bomb did not explode upon contact with the plane. It immediately burst into flames. The pilot maintained level flight for about 15 seconds; then the ship dropped off on the left wing for about 1000 feet, then exploded. When the explosion occurred, one man was blown out of the ship; his chute was burning and never opened. The tail turret was blown off and later exploded. I tried to follow the bigger pieces to the ground, most of which were still burning and exploding in the air. I did not see any large pieces hit the ground.

From the statement given by Arthur J. Darling, T/Sgt, Air Corps, 436th Bombardment Sq. (H):

On or about October 28, 1943 at approximately 1217 hours, I, Arthur J. Darling, 17037524, T/Sgt, 436th Bombardment Squadron (H) AAF, while flying as Aerial Engineer in Airplane #69 did observe the following: We were turning off our bomb run and the 2nd element was still on the run. A few seconds after the 2nd element's bombs were away I noticed three ships above them crossing over our 2nd element. I only saw two bombs drop, one of which fell directly on #5 ship, at the base of #2 engine. The bomb fell right through and the wing burst into flames. The ship maintained level flight for 15 to 20 seconds and fell off on the left wing burning more as it fell. I did not see it hit the ground.

After these depositions, a statement was sent to Gil's mother, Magdalene Barrett Rutherfurd, on December 9, 1943 from John B. Cooley, Colonel, A.G.D, Air Adjutant General. It reads, in part:

The Adjutant General notified you on November 3rd that your son, Second Lieutenant Lawrence G. Cook, was reported missing in action since October 28th over Burma.

Further information has been received that Lieutenant Cook was a crew member of a B-24 Liberator bomber which participated in a combat mission to Southern Burma on October 28th. The report states that during the mission his plane was seem to sustain damage from an accidental bomb explosion and to fall to the earth. This occurred at about 1:20 p.m. over Southern Burma.

Because of reasons of military security, it is regretted that the names of those who were on the plane and addresses of their next of kin cannot be furnished at the present time.

This letter did not clarify that Gil's plane had been struck by a bomb dropped by an American plane. It also did not give Magdalene the news that her son was surely dead.

Jane also wrote to her Congressman, Roger C. Slaughter of Missouri, to ask for clarity on what had occurred. Congressman Slaughter made a request to the War Department on April 7, 1944 for more information about the downing of the plane.

When no response was received, Slaughter tried again, and a contentious string of communication ensued. On April 27, 1944, W.H.S. Wright, Aide to the Secretary of War, acknowledged to Congressman Slaughter that the plane was downed in a friendly fire incident, and rejected any assertion of a coverup. It was now six months after Gil and his crew had died.

In 2014, I filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the National Archives and was sent a packet of wartime correspondence related to the downing of Gil's plane that included the letter above. It also contained a letter from the Army's chaplin to Magdalene Barrett Rutherfurd expressing his sadness at the lack of information about her son. It included communication between Colonel Fitzpatrick and Lt. Col. Haddock of the Air Corps. discussing the need for more transparency to the families. The War Department knew the men were dead but had not stated as such to their families. Protocols needed to be followed and a lengthy period of investigation was required.

This left it to my grandmother to inform her aunt that her son was dead. Magdalene shared the information with Jane Luce. However, the War Department's reluctance to make an official statement about the deaths left the door open to a cruel hope, and the families spent many months in limbo. On 29 October 1944, J.A. Ulio, The Adjutant General, sent Magdalene a letter declaring Gil deceased. It had been a year since his death.Glenn, in a more serious light, I'm sorry to report that Lt. Cooke was killed in action. My old roommate wrote me from the squadron I was formerly in with Lt. Cooke that Lt. Cooke's plane was hit by a bomb in mid-air and shortly afterward his plane fell in flames to the ground. No one was seen to jump from the flaming ship.

This hurts me to report this, but I know you people would want the truth. I felt terrible about the whole incident. Gosh, how I liked Lt. Cooke and so did everyone else. Please, extend my heart felt sympathies to his family and LaVerne.

There were no bodies to send home in flag-draped coffins; no sons to bury in hometown graveyards. The sole memorial for Gil Cook is located in The Philippines, at the American Memorial Cemetery in Manila. It's located on the site of the former Fort William McKinley and was dedicated in 1960.

|

| This photo was taken by my brother at the American Memorial Cemetery |

The cemetery consists of a large graveyard filled with neat, white crosses. Beyond them is a memorial chapel flanked by two hemicycles of stone walls. Within these walls are mosaics detailing the various battles and campaigns in the Pacific Theater and China India Burma Theater during World War II, along with the inscribed names of the dead and missing. In the western hemicycle can be found the lists of the missing, divided by branch of armed services.

Today, I honor the service of Gil Cook and the eight other men who were lost on October 28, 1943. They were young and promising, in several cases the only sons or only children of their parents. They left behind grief stricken families and fiancees. The fact that I am writing about this incident and these deaths 77 years after they occurred indicates just how devastating these losses were to the families involved.

HERE ARE RECORDED THE NAMES OF AMERICANS

WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN SERVICE OF THEIR COUNTRY

AND SLEEP IN UNKNOWN GRAVES

1941-1945

1 Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/436th_Training_Squadron↩

No comments:

Post a Comment