|

| A map of Providence, Rhode Island in 1664, with the properties of original settlers shown. |

In my previous posts about two of my 9th great-grandfathers Samuel Gorton and Robert Coles, I mentioned another of my 9th great-grandfathers, William Carpenter, who lived in close proximity to Gorton and Coles in colonial Rhode Island. While Samuel and Robert were known for their unwillingness to conform, both in religion and in society, William Carpenter apparently lived an upstanding and controversy-free life as a founding settler of Rhode Island. He was the brother-in-law of Benedict Arnold, who served three times as the governor of Rhode Island, and William held a number of community roles during his lifetime. Rhode Island may have been the refuge of nonconformists and troublemakers, but for the Carpenter and Arnold families, it was a place to build a new and idealistic community and serve that community in leadership.

William Carpenter was born in 1610 in Amesbury, Wiltshire, England. Amesbury is a small but scenic village located near the River Avon, and is known for being the home of Stonehenge, the world-famous prehistoric megalithic monument and archaeological site. Recently, Amesbury was also declared to be England's oldest settlement.

Carbon dating of bones of aurochs – the giant cattle that were twice the size of today's bulls – at the Blick Mead dig site, has shown that Amesbury has been continually occupied for each millennium since 8,820BC. Older than Thatcham, occupied since 7,700BC, it is in effect where British history began. [source: The Guardian]

Little is known of William's early years. His father was Richard Carpenter, likely from Amesbury or the area immediately surrounding it in Wiltshire, but his mother is not known.

In 1634, William married Elizabeth Arnold. Elizabeth, who was born about 1611 in Ilchester, Somerset, England, was the daughter of William Arnold and Christiana Peak. In the early 1600s, her father, William Arnold served as the warden of St. Mary's Church in Ilchester.

|

| A contemporary view of St. Mary Major in Ilchester |

[William] Arnold had been important to his church in England, and Samuel Gorton writes in Simplicity's Defence that Arnold had been a great professor of religion in the west of England. Once in the New World, he became one of the original 12 members to organize the first Baptist Church in Providence, founded by Roger Williams in 1638. This church was also the first Baptist church established in America. [source: Wikipedia]

It is unknown how William Carpenter and Elizabeth Arnold met. Ilchester and Amesbury are about an hour apart via car in the modern day, so it would have been a much longer journey in the 1600s. However, Ilchester was a market town, and it's possible that William went there on business of some sort. The Arnolds were influential in Ilchester and it's likely that William and Elizabeth settled near them after their marriage.

|

| The distance between Amesbury and Ilchester, southwest of London |

Elizabeth had two brothers, Stephen and Benedict, and one sister, Joanna. She also had two first cousins that were close with her family, Frances Hopkins and Thomas Hopkins, the children of Elizabeth's late aunt, Joanna Arnold Hopkins.

In 1635, the Arnold family decided to leave England and settle in the American colonies. No exact reason for this decision has been recorded, but most religious figures departing England at that time were Puritans who hoped to create churches that reformed the problems they saw in the Church of England.

Beginning in 1630 as many as 20,000 Puritans emigrated to America from England to gain the liberty to worship God as they chose. Most settled in New England, but some went as far as the West Indies. Theologically, the Puritans were "non-separating Congregationalists." Unlike the Pilgrims, who came to Massachusetts in 1620, the Puritans believed that the Church of England was a true church, though in need of major reforms. Every New England Congregational church was considered an independent entity, beholden to no hierarchy. The membership was composed, at least initially, of men and women who had undergone a conversion experience and could prove it to other members. Puritan leaders hoped (futilely, as it turned out) that, once their experiment was successful, England would imitate it by instituting a church order modeled after the New England Way. [source: Library of Congress]

Elizabeth's brother, Benedict Arnold, a future President and Governor of Rhode Island, wrote a memoir later in his life. In it he recalled his family's journey to America.

Memorandom my father and his family Sett Sayle ffrom Dartmouth in Old England, the first of May, friday &. Arrived In New England. June 24° Ano 1635. Merom. We came to Providence to Dwell the 20th of April 1636. per me Bennedict Arnold.

Together on this journey were William Arnold, his wife Christiana, and their four children, daughters Elizabeth (23) and Joanne (17), and sons Benedict (19) and William (12). They were accompanied by Elizabeth's husband, William Carpenter, Elizabeth's cousins, Thomas Hopkins (19) and Frances Hopkins (21), and Frances Hopkins' husband, William Mann. Also traveling with them were a family from nearby Yeovil, in Somerset. They were Stukeley Westcott and his wife Juliana, along with their six children. The relationship between the Arnold and Westcott families is unclear, but one of the Westcott children on that voyage, Damaris, would later marry Benedict Arnold in Rhode Island. The Arnold and Westcott families departed from Dartmouth, England on May 1, 1635 and arrived in Massachusetts on June 24, nearly a two-month journey across the Atlantic Ocean.

In mid-1635, Massachusetts saw a great influx of emigrants from England. In June and July alone, at least fifteen ships arrived carrying new settlers. However, William Carpenter, my 9th great-grandfather, was the first person with the surname Carpenter to permanently settle in the American Colonies.

The Arnold and Carpenter families lived first at Hingham, Massachusetts, about 15 miles south of Boston. They were in Hingham for less than a year, however, and soon moved on to Providence, Rhode Island, where they arrived on April 20, 1636.

|

| An artist's rendering of Roger Williams arriving in Providence, greeted by the Narragansett people |

Providence Plantation was founded by Roger Williams and five fellow settlers sometime in the Spring of 1636. As mentioned in previous posts, Roger Williams was banished from Massachusetts in 1635 due to his strong belief in the separation of church and state, something that ran counter to the very foundations of society in Massachusetts. The original Pilgrims and the Puritans that followed had come to the colonies specifically to create a godly society, and religion was at the center of their civic life. After his banishment, Roger Williams moved south into Narragansett territory, across the Sekonk River from Plymouth Plantation, where Massachusetts authorities had no jurisdiction. With Williams were four other men, William Harris, John Smith, Francis Wickes, and Thomas Angell. They were joined shortly thereafter by Joshua Verin, and the group negotiated with the Narragansetts for land in March 1636.

The Arnolds and Carpenters arrived in Providence in April 1636. The connection between the Arnold/Carpenter family and Roger Williams isn't clear, but given how closely they followed Williams' path to Providence, it seems likely that they encountered each other in Massachusetts.

William Carpenter and William Arnold's names are listed as original proprietors of Providence in a deed created by Roger Williams on October 8, 1638. There were fourteen men noted on this deed:

- Roger Williams

- Stukeley Westcott

- William Arnold

- Thomas James

- Robert Coles

- John Greene

- John Throckmorton

- John Sweet

- William Harris

- William Carpenter

- Thomas Olney

- Francis Weston

- Richard Waterman

- Ezekiel Holyman

Included in this list was Stukeley Westcott, who had accompanied the Arnolds on their journey from England to the colonies. The Westcotts had initially gone to Salem after arriving in Massachusetts, and likely crossed paths with Roger Williams, who lived in Salem until his ouster in 1636. The Westcotts relocated to Providence in 1638, reuniting with the Arnold and Carpenter families. Also on this list of founders is my 9th great-grandfather,

Robert Coles, who was at that point on a redemptive path after years of destructive behavior in Massachusetts.

The land that Roger Williams, and shortly thereafter, the Arnolds and Carpenters setttled, in modern-day Providence, was then the home of the Narragansett people. In his book The Arnold memorial; William Arnold of Providence and Pawtuxet, 1587-1675, and a genealogy of his descendants (pub. 1935), author Elisha Stephen Arnold said that William Arnold, "...felt for the Indians a conscientious kindliness and in his dealings with them was actuated by a sense of strictest justice." William Arnold, like Roger Williams, learned the Narragansett language and acted as interpreter for the native people with the English settlers on many occasions.

The Arnold contingent spent only a short time in Providence proper. They soon relocated about four miles south of town, along the Pawtuxet River. William Arnold was the first Englishman to settle in Pawtuxet, which later became the town of Cranston. He built a home in the wilderness about a mile north of the Pawtuxet Falls and was shortly followed by William Harris, William Carpenter, and Zachariah Rhodes (William's son-in-law). Rhodes and his brother-in-law Stephen Arnold built a grist mill near the falls and laid out what became known as the Arnold Road, which headed northward from Pawtuxet to join the Pequot Trail.

In 1639, William Arnold was one of twelve men who founded the first Baptist church in America.

This church still exists and holds regular services. It is located at 75 North Main Street in Providence. While the church's website only mentions Roger Williams as their founder, in reality, it was a group effort that involved most of Providence's founding fathers. Church founders included Thomas Olney and Ezekiel Holyman. Holyman was the person who later baptized Roger Williams at the church. The group also included William Arnold, known throughout England and the Providence colony for his thoughtful study and practice of religion. As a religious leader and prominent landowner in the new settlements of Providence and Pawtuxet, Arnold held an important role in the community.

William Carpenter was also very involved in civic life. He was a carpenter by trade and built some of the homes in the Pawtuxet, including his own. He also acted as an surveyor of sorts, laying out paths for roads and bridges, and drawing boundary lines. He was appointed by Boston authorities as one of four men designated to keep the peace in Pawtuxet. He served as a commissioner and deputy for Providence to Rhode Island's General Court Assembly, acted as a warden (magistrate) in the General Court of Trials, served as town meeting moderator, and was elected to the Providence town council, just to name some of his roles. He also seems to have been a minister, as he performed the marriage ceremony for his daughter Priscilla to William Vincent.

William Carpenter and Elizabeth Arnold Carpenter raised their eight children in Pawtuxet.

- Joseph Carpenter (b. 1635, d. 1683, m. (1) Hannah Carpenter (2) Anna Weeks)

- Lydia Carpenter (b. 1638, d. 1711, m. Benjamin Smith)

- Ephraim Carpenter (b. 1640, d. 1703, m. Susannah Harris)

- Timothy Carpenter (b. 1643, d. 1726, m. Hannah Burton)

- William Carpenter (b. 1645, d. 1676)

- Priscilla Carpenter (b. 1648, d. 1690, m. William Vincent)

- Silas Carpenter (b. 1650, d. 1695, m. Sarah Arnold)

- Benjamin Carpenter (b. 1653, d. 1711, m. Mary Tillinghast)

Joseph Carpenter's wife was Hannah Carpenter, daughter of William Carpenter and Abigail Briant of Rehoboth, Massachusetts. While they had the same surname, they were not related.

Priscilla's husband, William Vincent, was her first cousin, the son of Frideswide Carpenter Vincent, William Carpenter's sister.

Silas Carpenter's wife, Sarah Arnold, was the granddaughter of William Arnold and Christiana Peake, by their son Stephen. This means Silas and Sarah were first cousins once removed.

In 1640/1641, Providence, and the Arnolds/Carpenters by extension, faced one of the biggest problems to bedevil their new community. It was the arrival of my 9th great-grandfather Samuel Gorton, whose tumultuous journey through Rhode Island I chronicled in

a previous post. The Arnolds and Carpenters were not fans of Gorton, to say the least.

|

| Samuel Gorton. Not the most popular man in Rhode Island. |

Having been banished from Aquidneck, Samuel Gorton and his followers came to Providence, where Gorton immediately made himself known by refusing to follow local regulations and stirring up the populace with his radical religious beliefs. Roger Williams did not allow Gorton to be recognized as a Providence resident, since Gorton fundamentally disagreed with the governmental systems Williams had created there.

The differences between Williams and Gorton were not on religious grounds but on the question of the concept of government. Gorton, in 1641, again attempted to be received in “town fellowship,” and again he was refused. The man who most strenuously opposed Gorton’s application at this time was William Arnold, who asserted that Gorton was “an insolent, railing and turbulent person” and that he had divided Providence “into parties aiming to drive away its founders.”

The bitter feelings that grew between Arnold and Gorton lasted for the lifetime of both men and were responsible for many of the disturbing events of the early period. Serious difficulties arose in Providence in November 1641, when a group of “eight men orderly chosen” rendered a decision against one of Gorton’s followers, Francis Weston, and attempted to confiscate his cattle. The Gortonists, which included Gorton, John Greene and Randall Holden, rallied behind Weston and rescued him and his cattle. A riot occurred as a result and blood was shed. Arnold and 12 others protested, and when Gorton and his followers moved into the Pawtuxet area three of the original Pawtuxet purchasers, William Arnold, Robert Cole and William Carpenter, as well as Benedict Arnold, William Arnold’s son, offered themselves and their land to the protection of Massachusetts in September 1642. [Source: Warwick Beacon, 2011]

When

I wrote about Samuel Gorton, I reviewed a number of sources relating to the events that led up to the fateful raid on Shawomet. This assault by Massachusetts authorities resulted in the deaths of two women and the arrest and imprisonment of Gorton. What I did not fully realize at that time was that this raid was in fact a direct result of efforts by my Arnold, Coles, and Carpenter ancestors to take down Gorton.

The Arnolds, Coles, and Carpenter were highly offended by Gorton, who had moved with some of his adherents to Pawtuxet. They went to Boston and submitted themselves to the government and jurisdiction of Massachusetts on September 2, 1642. They were received by the General Court there and appointed justices of the peace. In doing this, these settlers allowed a foreign jurisdiction into the midst of the Providence government, a condition that lasted for 16 years. Gorton was unhappy about being under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts and moved with his followers another 12 miles (19 km) farther south, settling beyond the limits of Massachusetts' jurisdiction at a place called Shawomet.

[Benedict] Arnold and his father had already become proficient in the Narragansett and Wampanoag languages, and both harbored an intense dislike of Gorton. They devised a scheme to undermine their adversary and to simultaneously obtain extensive lands from the local Indians. Gorton had purchased Shawomet from Miantonomi, the chief sachem of the Narragansett people. Minor sachems Ponham and Sacononoco had some control of the lands at Pawtuxet and Shawomet, and Arnold, acting as interpreter, took these chieftains to Governor John Winthrop in Boston and had them submit themselves and their lands to Massachusetts, claiming that the sale of Shawomet to Gorton was done "under duress." Now with a claim to Shawomet, Massachusetts directed Gorton and his followers to appear in Boston to answer "complaints" made by the two minor sachems. When Gorton refused, Massachusetts sent a party to Shawomet to arrest him and his neighbors. [Source: Wikipedia]

Gorton would ultimately be redeemed, but my Arnold and Carpenter ancestors were surely relieved that their plan to remove him from Rhode Island was, at least temporarily, successful. They would never fully be rid of him, though. Upon his return in 1648 to Shawomet, which was then renamed Warwick, Samuel Gorton had enough influence to be acknowledged as a major political figure in Rhode Island for the rest of his life.

Benedict Arnold and his wife and children left Providence in 1651 to settle in Newport. In 1657, he was named President of the Rhode Island colony, succeeding Roger Williams. His father, William Arnold and his brother in law, William Carpenter, stayed in Pawtuxet with their families. [Note: Benedict Arnold was the great-grandfather of the infamous turncoat

Benedict Arnold (1741-1801) who betrayed George Washington and defected to the British army during the Revolutionary War.]

In 1658, Providence and Pawtuxet formally reunited. This period was a calm and peaceful one for the Providence community, and the Arnolds and Carpenters enjoyed nearly two decades without notable strife. This ended in dramatic fashion in 1675 with the start of King Philip's War, which was to devastate Rhode Island and all of the New England colonies.

|

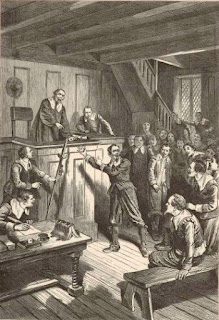

| A colored woodcut from the 19th century depicting a scene from King Philip's War |

King Philip’s War—also known as the First Indian War, the Great Narragansett War or Metacom’s Rebellion—took place in southern New England from 1675 to 1676. It was the Native Americans' last-ditch effort to avoid recognizing English authority and stop English settlement on their native lands. The war is named after the Wampanoag chief Metacom, later known as Philip or King Philip, who led the fourteen-month bloody rebellion. [Source: History.com]

The war ravaged the New England region. Rhode Island was somewhat unique among the colonies in its relations with Native Americans. Roger Williams, from his earliest days in Rhode Island, advocated for fair treatment of Native Americans and Rhode Island's English settlers endeavored to live in peaceful coexistence with their Narragansett neighbors. In June 1675, the Wampanoag chief Metacom launched a series of raids on colonial towns, killing residents and burning homes. Initially, Rhode Island's leaders made efforts to maintain neutrality and negotiate peace, and the Narragansett people did not join the Wampanoags in their conflict with the English. However, both groups were inexorably drawn into the conflict as the violence spread.

On December 19, 1675, the Great Swamp Massacre took place in what is now West Kingston, Rhode Island. On that day, colonial militia forces preemptively attacked the Narragansett fort in order to prevent them from aligning with the Wampanoags. Somewhere between 300-600 Narragansetts were killed, including women, children, and the elderly. This shocking and unprovoked attack outraged the Narragansetts and brought them fully into the conflict. They joined forces with the Wampanoags and the allied Native American fighters began a campaign of destruction in Rhode Island. Over the next several months, the cities of Warwick, Providence, and Wickford were burned to the ground.

|

| A rendering of the burning of Providence |

On January 27, 1676, William Carpenter's property was raided by a Native American group led by Canonchet, a Narragansett Sachem. It has been written that William Carpenter's son, William Jr., was killed during this attack. These accounts claims that William Carpenter built a block house that provided a strong defense against attacks, and his family and neighbors sheltered there while attempting to fight off a Native American assault in January 1676, but William Jr. and a household servant were both killed in the effort. This is not proven, however. William Jr. did die in January 1676, at age 23, but it's not conclusively known what caused his death.

On March 29, 1676, the Wampanoag forces sacked Providence, where the Arnold and Carpenter families were living. Having had advance warning that the Native American soldiers were approaching, all but about 30 of Providence's 500 residents fled to Aquidneck Island. 77-year old Roger Williams remained with a small group of men to face the attackers. The names of those who stayed with him were not recorded. It's possible that William Carpenter was among them, at age 66, or perhaps some of his sons. William Arnold was not there, having died the previous year. According to legend, Williams tried to reason with the Native Americans as they destroyed the town he founded.

As Providence burned, a group of Native Americans from several tribes assembled on the banks of a salt cove across from the town. Williams walked out to talk with them across the water, his back to the burning town. The conversation between the warriors and the old minister lasted an hour. Roger Williams asked them why they burned and killed their kind neighbors. He told them, "This house of mine now burning before mine eyes hath lodged kindly some thousands of you these ten years." They said Rhode Island had joined the other colonies in the Great Swamp massacre. In a letter to his brother, Williams recounted his reply: I told them they … "had forgot they were mankind and ran around the country like wolves tearing the innocent and peaceable….They confessed they were in a strange way." Roger Williams then warned them that it was almost time to plant. The Indians said they didn’t care about planting; they would take food from the English. They argued some more, and finally Williams suggested he intervene to make peace. The Native Americans said they would spend the next month burning Plymouth Colony, and then they would talk to him. But they never used Rogers Williams’ services as a peacemaker. They did, however, tell him the safe way home. [Source: New England Historical Society]

Rhode Island's colonial government was unable to stop the bloodshed. However, on April 4, 1676 the General Assembly specifically requested the guidance of William Carpenter. " It was voted, that in these troublesome times and straits in the colony this assembly desiring to have the advice and concurrence of the most judicious inhabitant, do desire at there next sitting the company and counsel of William Carpenter." It's not known exactly what William might have done to help. The war ground on until August, when Metacom was killed. This brought an end to the violence, although a treaty marking the official end of the war would not be signed until April 1678.

After the war ended, William Carpenter returned to Providence and built a new home. Other family members who rebuilt in Providence included William's son Timothy with wife Hannah Burton, his daughter Priscilla with husband William Vincent, his son Silas with wife Sarah Arnold, his son Benjamin with wife Mary Tillinghast, his brother-in-law, Stephen Arnold with wife Sarah Smith, and his sister-in-law, Joanna Arnold Rhodes with husband Zachariah Rhodes.

The war was the greatest calamity in seventeenth-century New England and is considered by many to be the deadliest war in Colonial American history. In the space of little more than a year, 12 of the region's towns were destroyed and many more were damaged, the economy of Plymouth and Rhode Island Colonies was all but ruined and their population was decimated, losing one-tenth of all men available for military service. More than half of New England's towns were involved in conflict. Hundreds of Wampanoags and their allies were publicly executed or enslaved, and the Wampanoags were left effectively landless. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Arnold and Carpenter families were actively involved in rebuilding Providence after the war. The original settlers of Providence were largely elderly by this point, however. Roger Williams died in 1683. William Carpenter died on September 7, 1685, at age 75. Elizabeth Arnold Carpenter died a year and a half later, on February 22, 1687. Elizabeth's brother, Governor Benedict Arnold, died in 1678, but her sister Joanna and brother Stephen outlived her, dying in 1692 and 1699, respectively. All left many descendants.

|

A sketch of Providence dating from the early 1800s.

|

The material goods present at William’s home were inventoried after his death and appraised at £22. Listed among his belongings were many carpenter’s implements, including various types and sizes of saws and augers; chisels, plane irons, gouges, drawing knives, and adzes; a wainscot plough; a burr (drill or chisel); and a spokeshave. Despite the modest value of William’s personal estate, his tax assessments (on land, livestock, and saw mill he owned with sons Silas and Benjamin), were among the highest in Providence.

William Carpenter wrote a will on February 10, 1680, but he added a codicil after the death of his eldest son Joseph in 1683. This codicil indicated that Joseph had passed away and left his bequest to Joseph's son, Joseph Carpenter, Jr. Almost all bequests that William Carpenter made were of land, rights to subsequent land divisions, and rights of commoning (entitlements to pasturage on and/or divisions of common land). The amount of land he owned and willed to his descendants amounted to hundreds of acres. Also, William made a provision for his wife, Elizabeth, so that she would continue to live in comfort. He made bequests to all his surviving children, his daughters Lydia Smith and Priscilla Vincent, and his sons Silas, Benjamin, Timothy, and Ephraim. He also willed items to five of his grandchildren, Ephraim Carpenter, Jr. and Susanna Carpenter (children of Ephraim Carpenter), William Carpenter (eldest son of the deceased Joseph Carpenter), and Simon Smith and Joseph Smith (sons of Lydia Arnold Smith).

Most of William's descendants remained in the area near Providence after his death. There are still family members there to this day. However, William's two eldest sons, Joseph and Ephraim, moved to the Oyster Bay, New York area in the 1670s and set up milling operations in Musketa Cove, now known as Glen Cove. This branch of the Carpenter family would remain in New York for the next 200 years. Only then would the descendants of my third great-grandmother, Eliza Jane Carpenter Griffin, begin moving west.