This is part two in a series about my Coleman and Dwyer ancestors.

|

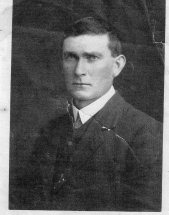

| John Dwyer, brother of Mary Dwyer |

In my last post, I talked about the Coleman family's origins in Ireland and where they settled in Australia. Now, I'm going to backtrack a bit to talk about the Dwyer family and how they arrived in Australia. The largely ill-fated union of Mary Dwyer and Andrew Coleman is approaching.

Mary Dwyer’s parents were John Dwyer and Johanna Burke. John Dwyer was born about 1816 in Mitcheltown, County Tipperary, Ireland. It is believed that his father was also named John Dwyer. Johanna Burke was born about 1834 in Ireland, presumably near Mitcheltown in County Tipperary. Her parents are said to be a George Burke and Kate Burke although I do not have conclusive proof of this. Burke and Dwyer were both very common names in County Tipperary at the time and records from the period are sparse.

John was about eighteen years older than Johanna. If this was his second marriage, I don’t have any information about the first marriage. When he and Johanna sailed to Australia in 1854, they did not have children with them. Johanna was 20 and John was 38 on that voyage. Their ship, the Maitland, departed from Plymouth, Devon, England and after months at sea arrived in Hobart, Tasmania on September 16, 1854.

Mary Dwyer’s parents were John Dwyer and Johanna Burke. John Dwyer was born about 1816 in Mitcheltown, County Tipperary, Ireland. It is believed that his father was also named John Dwyer. Johanna Burke was born about 1834 in Ireland, presumably near Mitcheltown in County Tipperary. Her parents are said to be a George Burke and Kate Burke although I do not have conclusive proof of this. Burke and Dwyer were both very common names in County Tipperary at the time and records from the period are sparse.

John was about eighteen years older than Johanna. If this was his second marriage, I don’t have any information about the first marriage. When he and Johanna sailed to Australia in 1854, they did not have children with them. Johanna was 20 and John was 38 on that voyage. Their ship, the Maitland, departed from Plymouth, Devon, England and after months at sea arrived in Hobart, Tasmania on September 16, 1854.

The Potato Famine had ravaged County

Tipperary. Almost 70,000 people died in

the county between 1845 and 1850 particularly in the years 1849 and 1850. The

county population fell from 435,000 in 1841, to 331,000 in 1851 and to 249,000

in 1861. The rural population declined by two-thirds in that period and the

town population by nearly one-half. Charles Gavan Duffy, the Australian

politician and Irish nationalist wrote of the famine years:

The whole population was dependant on

agriculture. The great landlords totalled two or three hundred. The mass of the

country was owned by a couple of thousand others, who lived in splendour. The

peasants, almost all Catholic, did the work, and reaped a harvest in which they

never shared. Rent in Ireland meant the whole produce of the soil, except a

potato pit. The food of the peasants was potatoes with a little milk or salt.

One half of them lived in mud cabins of one room with no windows. The island

was the most ignorant and impoverished of all the Christian nations on earth. [source]

County Tipperary was at the forefront of an Irish

rebellion, rooted in outrage over British reluctance to do anything to ease the

Irish famine. From History.com:

At the height of the Potato Famine in

Ireland, an abortive nationalist revolt against English rule is crushed by a

government police detachment in Tipperary. In a brief skirmish in a cabbage

patch, Irish nationalists under William Smith O'Brien were overcome and

arrested. The nationalists, members of the Young Ireland movement, had planned

to declare an independent Irish republic, but they lacked support from the

Irish peasantry, who were occupied entirely with surviving the famine.

By the mid-19th century, the Irish

population, which suffered under the system of absentee landlords, had been

reduced to a subsistence diet based largely on potatoes. When a potato blight

struck the country in the 1840s, disaster ensued. Between 1846 and 1851, more

than one million people starved to death, and some two million people left the

country, mostly to America. With the desperate times of the famine came an

increased radicalism in the Irish nationalist movement.

In 1846, O'Brien formed, with John Mitchel,

the Irish Confederation, a branch of the Young Ireland movement dedicated to

freeing Ireland by direct action. By 1848, the group was calling for open

rebellion against the English, but Mitchel was arrested, convicted of sedition,

and transported to a prison colony in Australia before the revolt could begin.

Aggravated by the worsening potato famine and Mitchel's arrest, O'Brien

launched an unsuccessful uprising on July 29, 1848. He was arrested and

sentenced to death for treason, but his sentence was commuted to transportation

to the penal colony at Tasmania.

After the failure of the Young Ireland

revolt, many embittered Irish nationalists immigrated to the United States,

Australia, and Canada, where they redoubled their agitation against England.

This is the environment John and Johanna Dwyer

were living in prior to their emigration to Tasmania. Although they both survived the famine, they

were peasants and would have undoubtedly seen family and friends starve to

death, voluntarily emigrate to other countries or be forcibly transported to

Australia for crimes against the Crown. Life in Ireland in 1854 was one of poverty and limited options.

When John and Johanna Dwyer traveled to Tasmania,

they did so as bounty immigrants. This

term refers to people whose passage was subsidised or paid for through one of

the assisted immigration schemes that operated in the various states of

Australia to encourage immigrants to Australia. A colonist chose the emigrant from England or

Ireland and paid his or her passage to Australia. The emigrant would then work for

the colonist. The colonial government would reimburse the colonist a bounty

equal to the fare. After a certain

period of time, the bounty immigrant would be free to leave the colonist’s

employ and strike out on their own. This

is exactly what John and Johanna did. Their early years in Tasmania appear to have been spent in Deloraine,

where several of their children were born.

Later, they moved further north to Launceton, Port Sorell and Sassafras.

The official records of Tasmania at this time are

a little confusing in regards to the Dwyer family. I had difficulty finding birth records for

the children, and have never actually seen a birth registration for Mary

Dwyer. I was only able to conclusively

prove her parentage by using the information provided on her marriage license

in Melbourne.

- TIMOTHY DWYER, born unknown; died June 27, 1900 in Tasmania

- MARGARET DWYER, born July 13, 1855 in Tasmania

- CATHERINE ALICE DWYER, born July 12, 1857 in Deloraine, Tasmania. She married John Gaffney in 1885.

- HONORA DWYER, born February 15, 1858 in Deloraine, Tasmania; died June 14, 1941. She married Bryan Sheehan in 1879.

- HAROLD DWYER, born December 15, 1858 in Tasmania

- MARY DWYER, born September 25, 1861 in Tasmania

- JULIA MAUD DWYER, born August 9, 1865 in Port Sorrell, Tasmania; died May 19, 1890 in Tasmania.

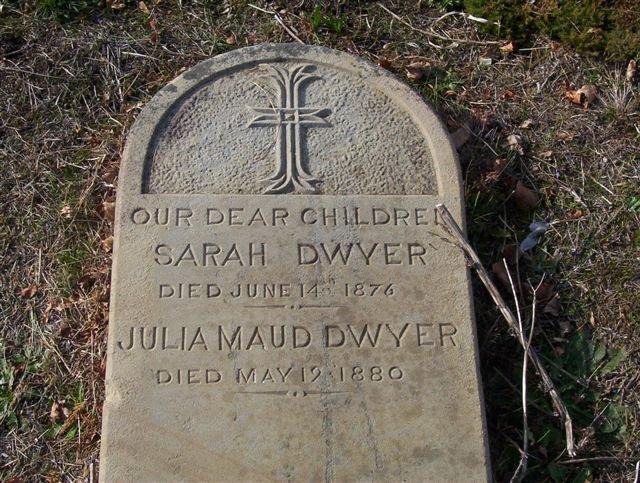

- SARAH DWYER, born about 1868 in Tasmania; died June 14, 1876 in Tasmania

- PHILIP DWYER, born about 1869 in Tasmania. He married Mary Steer in 1897.

- ELIZABETH ANN DWYER, born about 1873 in Tasmania; died June 3, 1880 in Tasmania

- JOHN DWYER, born November 15, 1878 in Launceton, Tasmania; died November 3 ,1954 in Gisborne, New Zealand. He married Irene Perkins.

Our relative Christine Bailey,

whom I met while researching our mutual ancestors, was able to find baptismal

records for some of the Dwyer children.

She sent me the following information from the Catholic Archives in

Tasmania:

Mary Dwyer, born September 25, 1861. Baptized

September 29, 1861. Sponsors: Thomas English and Julia English.

It's interesting to note that Thomas English

was also a witness to John Dwyer's will. Another witness was Bryan Sheahen,

a farmer in Sassafrass who married one of John and Johanna's daughters, Honora.

John Dwyer died November 10, 1887 in

Tasmania. In 1904, Johanna Dwyer married

for the second time, to Henry Cooke of

Tasmania. He had previously been married

to Honora O'Brien and had children from that marriage. Johanna was 70 years old at the time of her

second marriage. She died June 23, 1915

in Latrobe, Tasmania. She is buried in

Latrobe Cemetery, in the same plot as her first husband, John Dwyer and their

children, Sarah, Elizabeth and Julia.

|

| The grave of John and Johanna Dwyer, parents of Mary Dwyer |

|

| The grave of Sarah Dwyer and Julia Dwyer, sisters of Mary Dwyer |

No comments:

Post a Comment